Disruptors of Embryogenesis Reading

Download Notochord and Neural Tube Reading

Download Segmentation and Gut Tube Formation Reading

Notochord and Neural Tube

Recap: Fertilization to Gastrulation

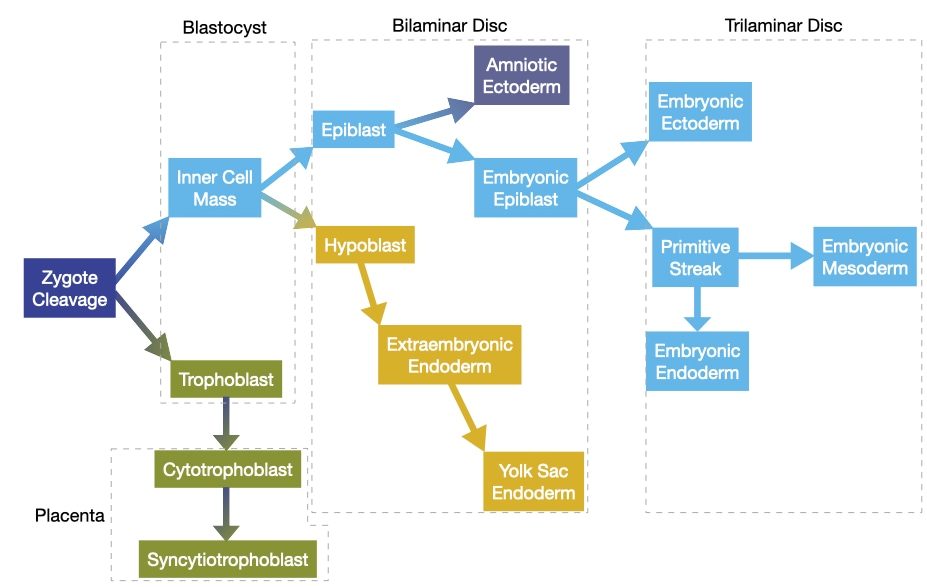

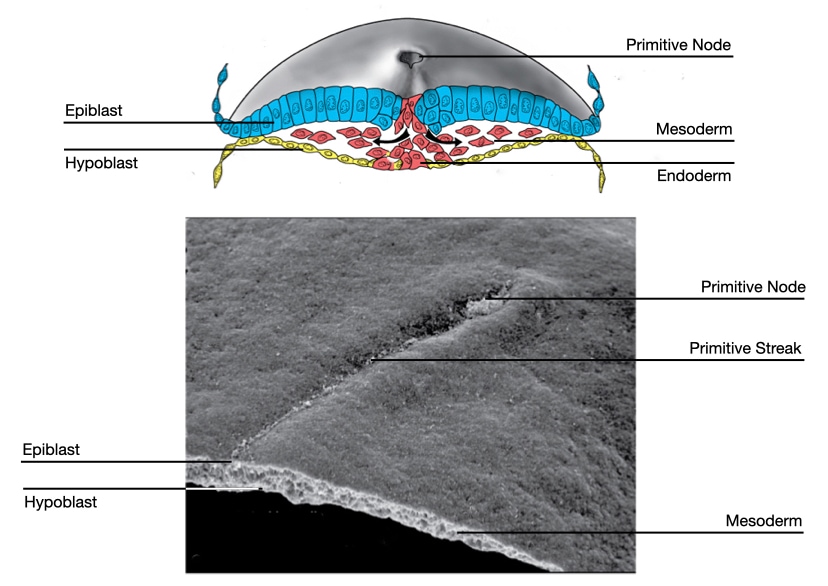

In the previous presentation, we discussed how a fertilized egg develops into blastocyst. Within the blastocyst a bilaminar disc develops that contains a layer of embryonic cells (epiblast) and a layer of non-embryonic cells (hypoblast). The bilaminar disc gives rise to a trilaminar disc that contains three embryonic tissues: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.

The major morphological event during this period is gastrulation in which a single layer of cells called the epiblast give rise to endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. During gastrulation, cells in the epiblast migrate toward the middle of the embryo and then descend toward the hypoblast layer. The first cells to descend will integrate into the hypoblast and become endoderm. The second set of cells to descend will remain separate from epiblast and hypoblast and become endoderm. Finally, cells that remain in the epiblast and do not descend will become ectoderm.

These events take place during the first three weeks of development.

- Day 1: Fertilized oocyte

- Day 5: Blastocyst forms

- Day 7: Blastocyst implants in uterine wall

- Day 9: Blastocyst fully implanted

- Day 12: Bilaminar disc

- Day 15: Primitive streak forms, start of gastrulation

- Day 17: Trilaminar disc

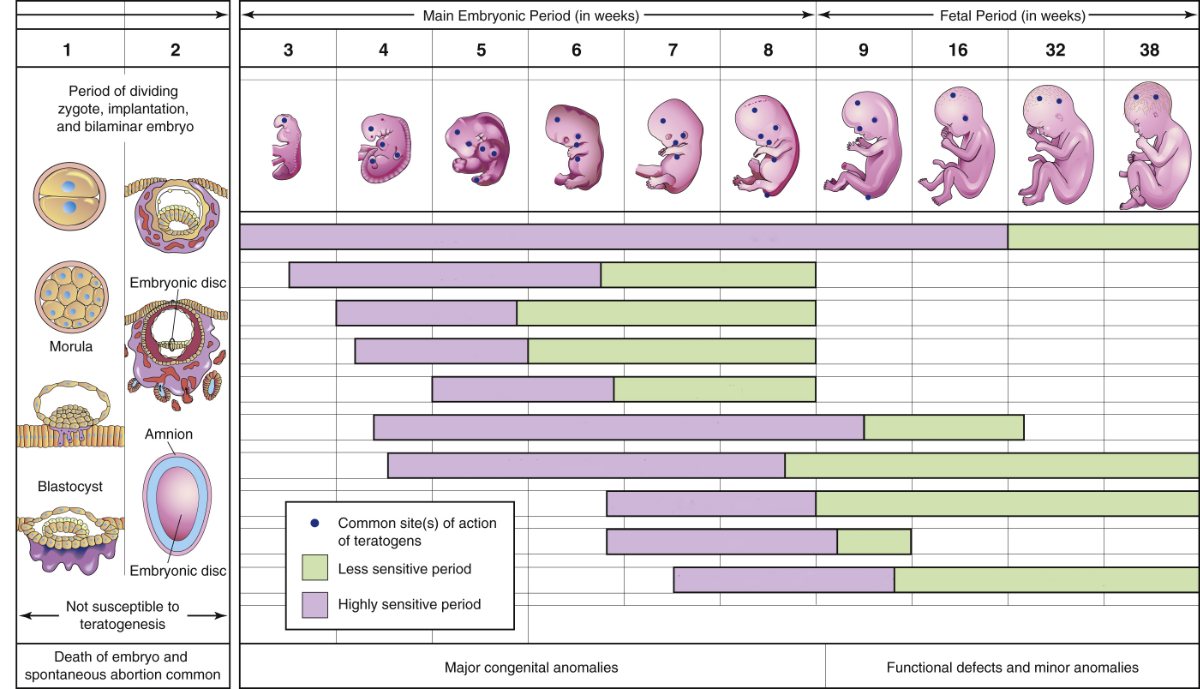

After formation of the trilaminar disc, the process of organogenesis begins and the embryo enters a perilous period. During this time, genetic mutations and environmental factors, called teratogens, can alter the development of the embryo and generate birth anomalies that can result in significant structural and functional changes that appear at birth or shortly after. The severity of these changes and their impact on the health of the newborn depend on which stage of organogenesis they affect. Changes in early stages, whether they arise from genetic or environmental causes, result in more severe anomalies.

The structures and organs also vary in their susceptible to genetic mutations and teratogens during embryogenesis. The chart below shows the estimated prevalence of some of the most common birth anomalies in the United States.

| Anomaly | Prevalence (per 10,000) |

|---|---|

| Anencephaly | 2.28 |

| Spina bifida | 3.65 |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | 5.83 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 5.80 |

| Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis | 10.41 |

| Cleft lip | 9.94 |

| Rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis | 4.59 |

You will discuss in more detail many of these anomalies in the courses where you learn about the organ systems affected by the anomaly.

This session will focus on the formation of the neural tube which is a precursor for the entire central nervous system. Mutations and environmental factors can cause a variety of anomalies, most commonly spina bifida and anencephaly, that vary in severity. A triumph of epidemiology was the discovery of the importance of folate in formation of the neural tube and its ability to reduce anomalies in the central nervous system during embryogenesis.

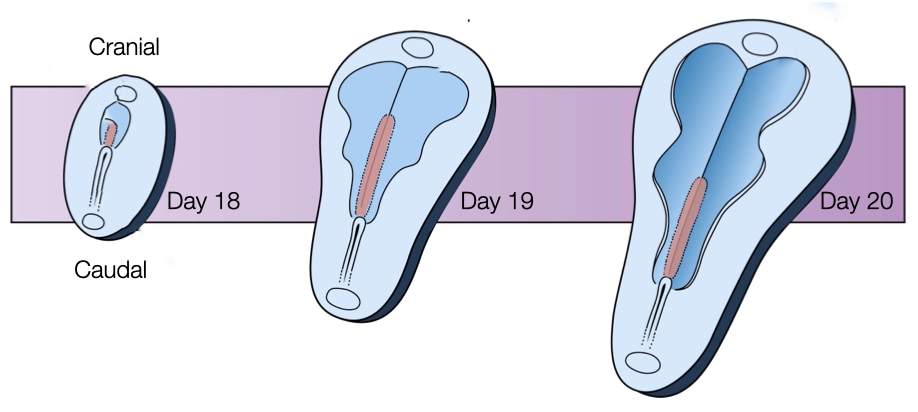

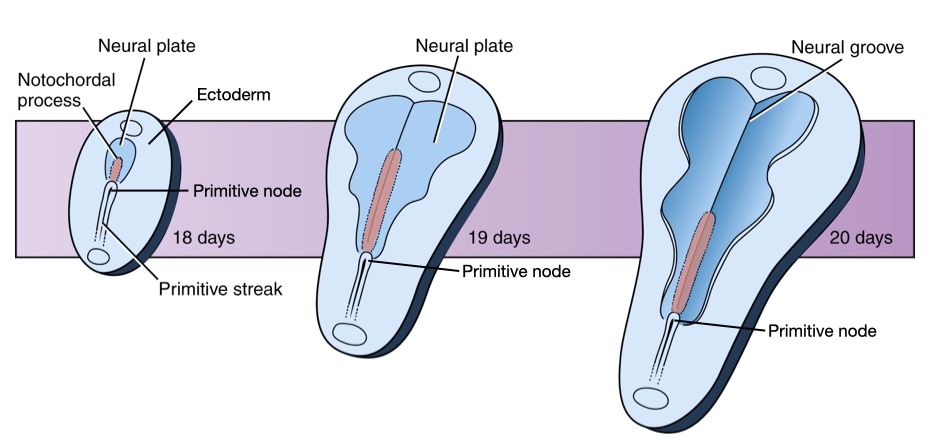

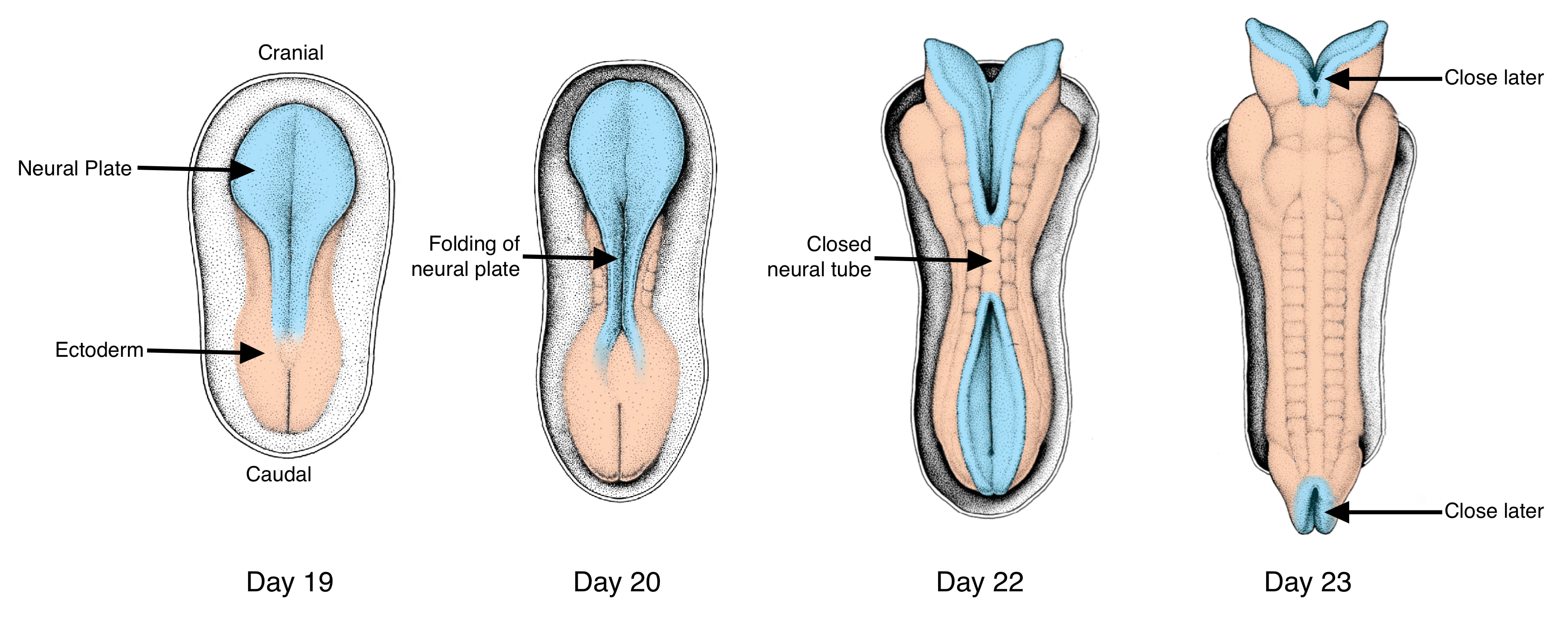

The formation of the neural tube occurs over several days and involves another structure called the notochord.

- Day 17: Notochord process

- Day 19: Notochord and neural plate

- Day 21: Neural tube closure starts

- Day 28: Completion of neural tube closure

Growth and Shape Change of the Embryo

A critical event in the formation of the neural tube is the growth and change in shape of the embryo. The embryo lengthens in the cranial-caudal direction and narrows laterally towards the caudal end. The lengthening of the embryo will allow for the formation of a tube along the cranial caudal axis. As described below, the lengthening of the embryo will be driven in part by its narrowing at the caudal end. Keeping the cranial end wide will provide the cellular material to form the structures that will develop into the brain.

Convergent Extension

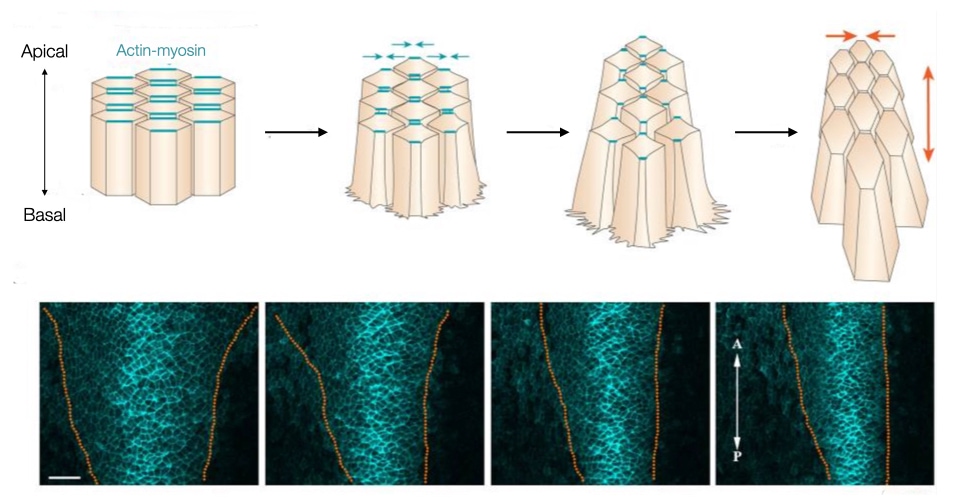

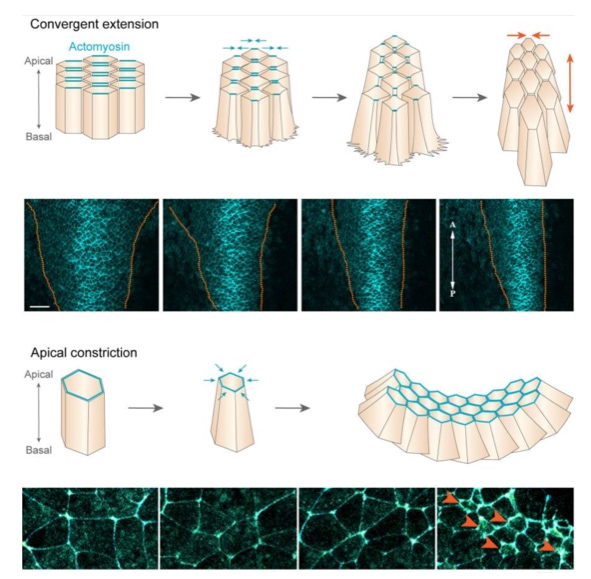

The growth and shape changes are driven by cell division and a process called convergent extension. How cell division leads to growth of the embryo seems clear: more cells means larger embryo and the rate of cell division is quite fast at roughly once per 10 hours. But shaping the embryo into a structure that elongates and narrows at one end (caudal) is driven by convergent extension. Through convergent extension a disc-like sheet of cells can elongate in one direction while narrowing in an orthogonal direction.

Convergent extension relies on a a property of epithelial cells called planar cell polarity. We are already familiar with polarity in epithelial cells based on their apical and basolateral surfaces. Recall that the basal surface attaches to the basement membrane whereas the apical surface faces the outside world or a fluid or air-filled space.

Planar cell polarity orients epithelial cells in the lateral direction. For example, a sheet of epithelial cells exposed to a concentration gradient of a specific signaling molecule will orient themselves in the direction of that gradient to generate polarity within the plane of the epithelial cells. One way to generate a concentration gradient is for cells along one edge of the epithelium to secrete a signaling molecule. As the signaling molecule diffuses from its source across the epithelium, its concentration decreases providing cells with a directional cue. The epithelial cells respond to that cue by localizing key proteins to side of the cell that faces the highest concentration of the signaling molecule and other proteins on the opposite side.

The distribution of proteins along opposite surfaces allows cells to change their shape in one direction. For example, actin and myosin filaments can be localized to the sides of the cell that lie along the concentration gradient. Contraction of the actin and myosin filaments along opposite sides of a cell narrows the cell on those sides and effectively narrows the entire sheet of cells in the direction of the concentration gradient of the signaling molecule. In addition, narrowing in one direction draws adjacent cells in that direction together and facilitates their interdigitation. By interdigitating cells drawn from a lateral direction, the sheet elongates in the orthogonal direction (caudally or posteriorly in the image).

The embryo uses convergent extension to extend in the caudal direction while narrowing on that side of the embryo. Cells from the lateral regions on the caudal side of the embryo migrate toward the center of the embryo. The result is an embryo that is narrower on the caudal side but also longer in the caudal direction. The bottom half of the figure above shows cells in the caudal end of an embryo labeled in blue. Over time (left to right) note how the embryo narrows due to convergent extension.

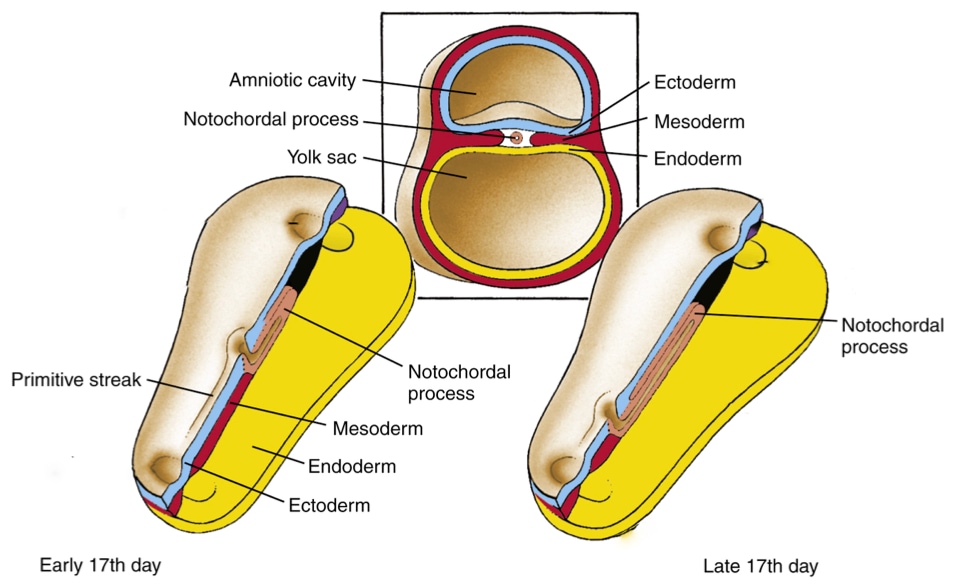

Notochord

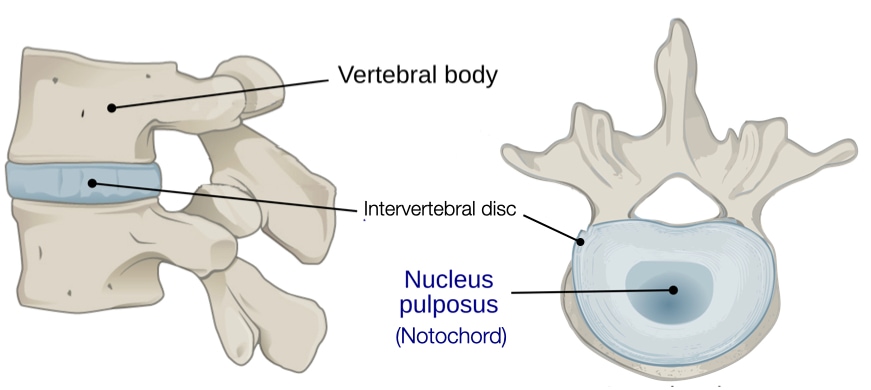

The first structure to form during development of the neural tube is the notochord, which is a tube-like collection of cells that form in mesoderm layer of the embryo. The notochord is an ancient structure that exists at one point during the development of all members of the Chordata family which includes all vertebrates. In humans and other mammals, the notochord exists for a short time during embryogenesis and then disappears. Some cells in the notochord become part of the intervertebral discs in the spinal cord of adults. The notochord plays a critical role in the development of the neural tube and the process of segmentation.

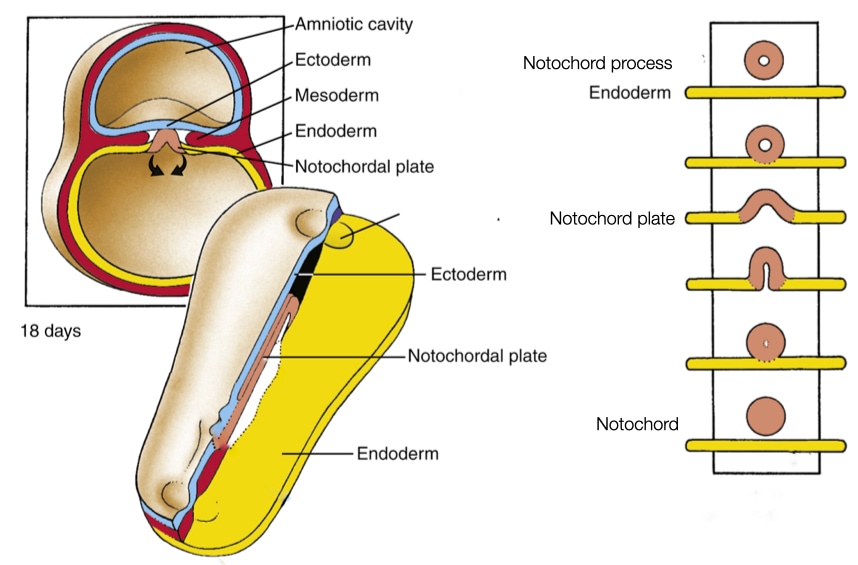

The notochord starts when a group of cells descends through the primitive pit and forms a tube-like structure, called the notochord process. The notochord process grows as more cells from the epiblast migrate through the primitive node to join the tube. As convergent extension pushes the primitive node toward the caudal end of the embryo, a trail of notochord process is left in its wake.

At some point the notochord process fuses with the underlying endoderm to form a linear strip of cells within the endoderm called the notochord plate. Why would the notochord process, which is tube and will develop into a tube (notochord), fuse with the endoderm? The answer appears to be that certain cells in the notochord plate play a critical role in setting up left-right polarity in the embryo and future body.

Left-Right Asymmetry

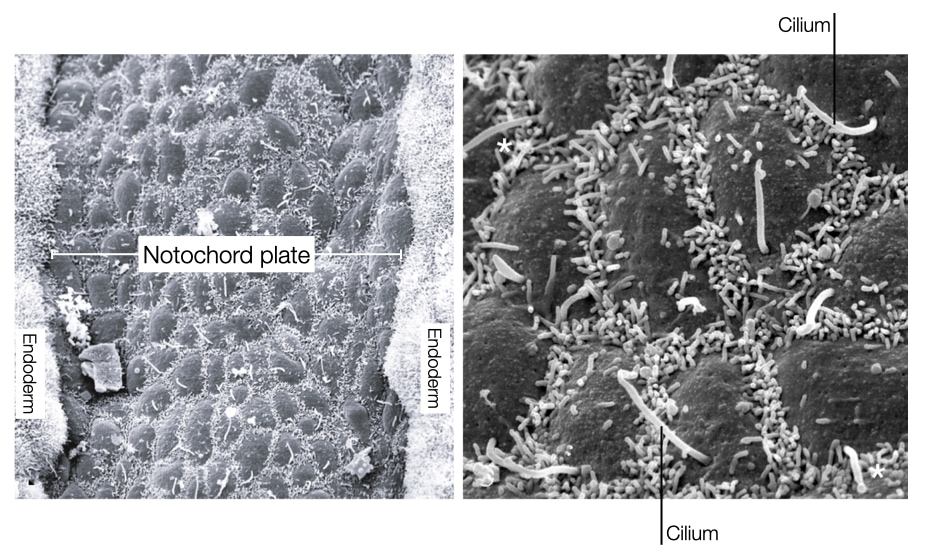

Many of the organs in our body are localized to one side, creating a left-right asymmetry. This asymmetry is established early in development after the notochord process fuses with the endoderm to form the notochord plate. Left-right asymmetry in the embryo is generated by the movement of signaling molecules to one side of the embryo. To directionally move the signaling molecules, cells toward the caudal end of the notochord plate express cilia on their surface.

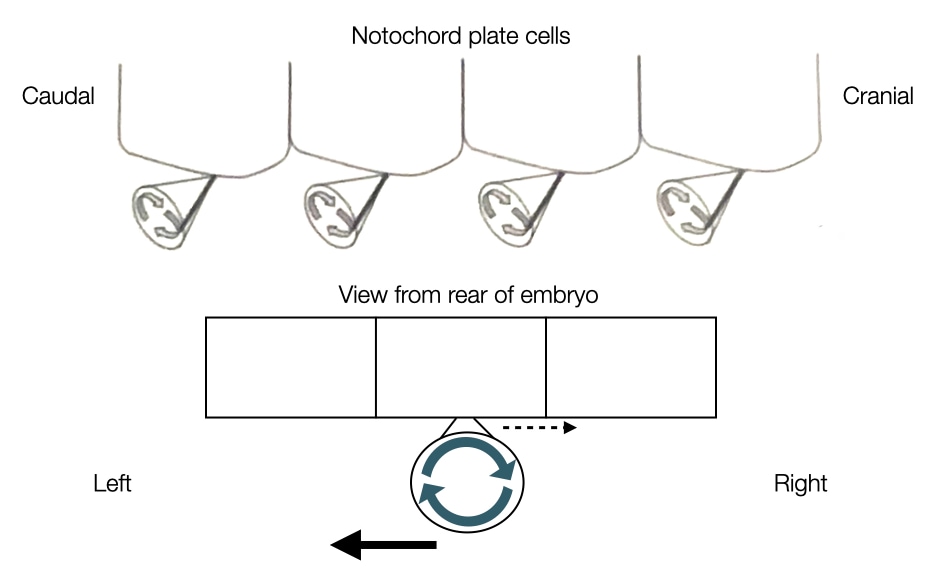

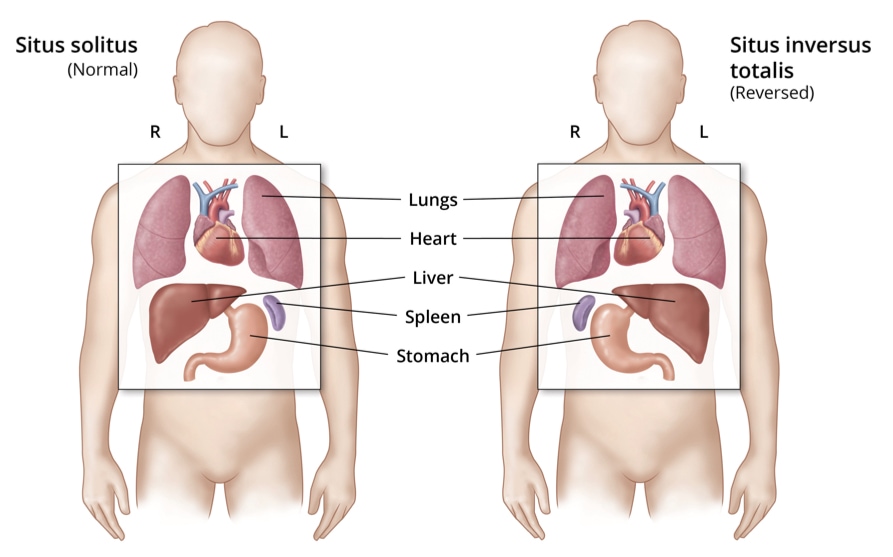

The orientation and rotational direction of the cilia in the notochord plate cells generate directional flow of fluid in the embryo. The cilia in the notochord plate cells are oriented toward the caudal side of the embryo and rotate in clockwise direction. The rotation of cilia pushes fluid both rightward and leftward, but because of the angle of the cilia, the rightward flow of fluid is slowed due to drag exerted by the cell body. In contrast, the leftward flow is further away from the cell body and does not feel the same drag. As a result, the net flow of fluid is in a leftward direction across the notochord. The leftward flow of fluid moves signaling molecules such as nodal to the left side of the embryo. This asymmetric distribution of nodal leads to development of certain organs on the left side of the body and others on the right.

Mutations that affect the structure and function of cilia in notochord cells lead to a condition called situs inversus in which organs that are normally on the left develop on the right and vice versa. The condition has few physiological consequences.

Eventually, the cells in the notochord plate separate from the endoderm to reform a tube called the notochord (see above). The cells in the notochord secrete signaling molecules, such as sonic hedgehog, that will pattern the spinal cord (see below). In most animals, the notochord disappears but some cells in the notochord form part of intervertebral discs that reside between vertebrae and give the spine flexibility and mechanical strength. Specifically, notochord cells are found in the central region of the disc called the nucleus pulposus which contains water, type II collagen, and proteoglycans.

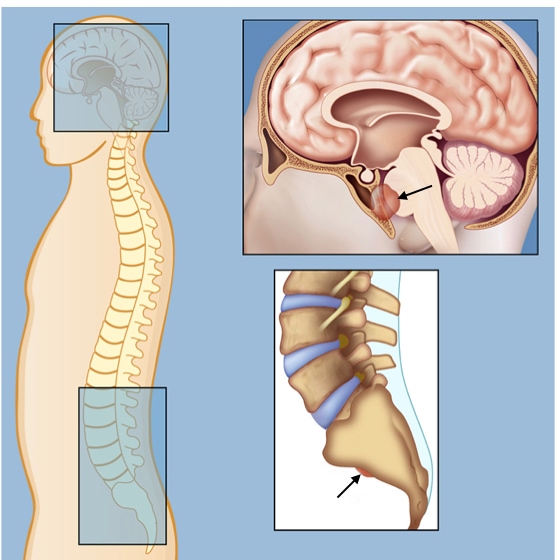

These notochord-derived cells are responsible for a rare tumor called chordoma which can develop anywhere along the spine. Chordomas are slow growing tumors that are usually detected in people 50 years and older. Symptoms vary based on where along the spinal cord the chordoma develops. Chordomas are treated by surgery and radiation therapy, but their proximity to the spine makes treatment challenging.

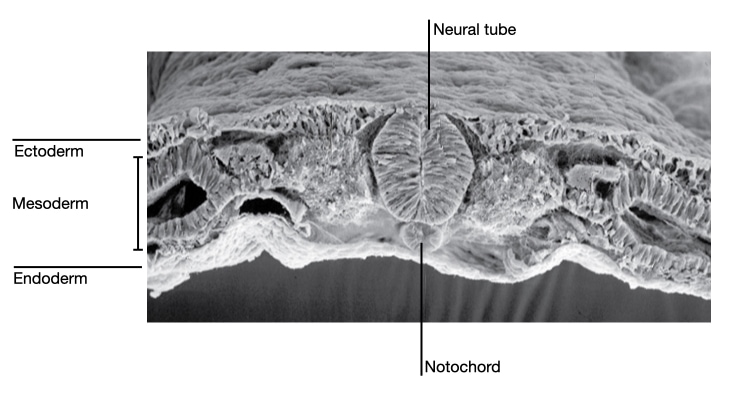

Neural Tube

The neural tube will give rise to structures in the central nervous system including the brain and spinal cord. The neural tube forms early in development, before most other organ systems, probably due to the complexity of brain and the need to have neural precursors ready to innervate organs when they start to develop.

Neural plate

The neural tube arises from a group of cells in the ectoderm called the neural plate. Cells in the ectoderm are kept committed to become surface ectoderm (I.e., epidermis of skin) by the signaling molecule bone morphogenic protein (BMP) produced by cells surrounding the embryo. To divert cells in the ectoderm to a neural fate, the embryo needs to reduce the influence of BMP on cells in a specific region of the ectoderm. Cells in the primitive node secrete inhibitors of BMP (e.g., chordin) which bind to BMP and prevent it from associating with its receptor in cell membranes. The lower amount of available BMP in the ectoderm close to primitive node allows cells in that region to follow a neural fate.

The release of BMP inhibitors starts around day 18 during which the cranial end of the embryo is close to the primitive node. Cells close to the node will differentiate and follow a neural fate. As the embryo grows and lengthens, the cells that initially committed to the neural fate (day 18) divide to expand the population of neural cells near the cranial end of the embryo. The lengthening of the embryo pushes the primitive node closer to caudal end of the embryo. As the primitive node migrates, its release of chordin causes ectoderm cells near the node to commit to a neural fate. Because these cells have less time to divide, the region of cells committed to a neural fate is narrower at the caudal end of the embryo.

The result is a plate of cells, called the neural plate, in the center of the ectoderm which are committed to a neural fate. The plate is widest at the caudal end due to proliferation of cells with committed on day 18 and narrows toward the caudal end. The geometry defines the future structures of the central nervous system, including the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain of the brain in the cranial portion of the neural plate and the spinal cord in the caudal portion of the neural plate.

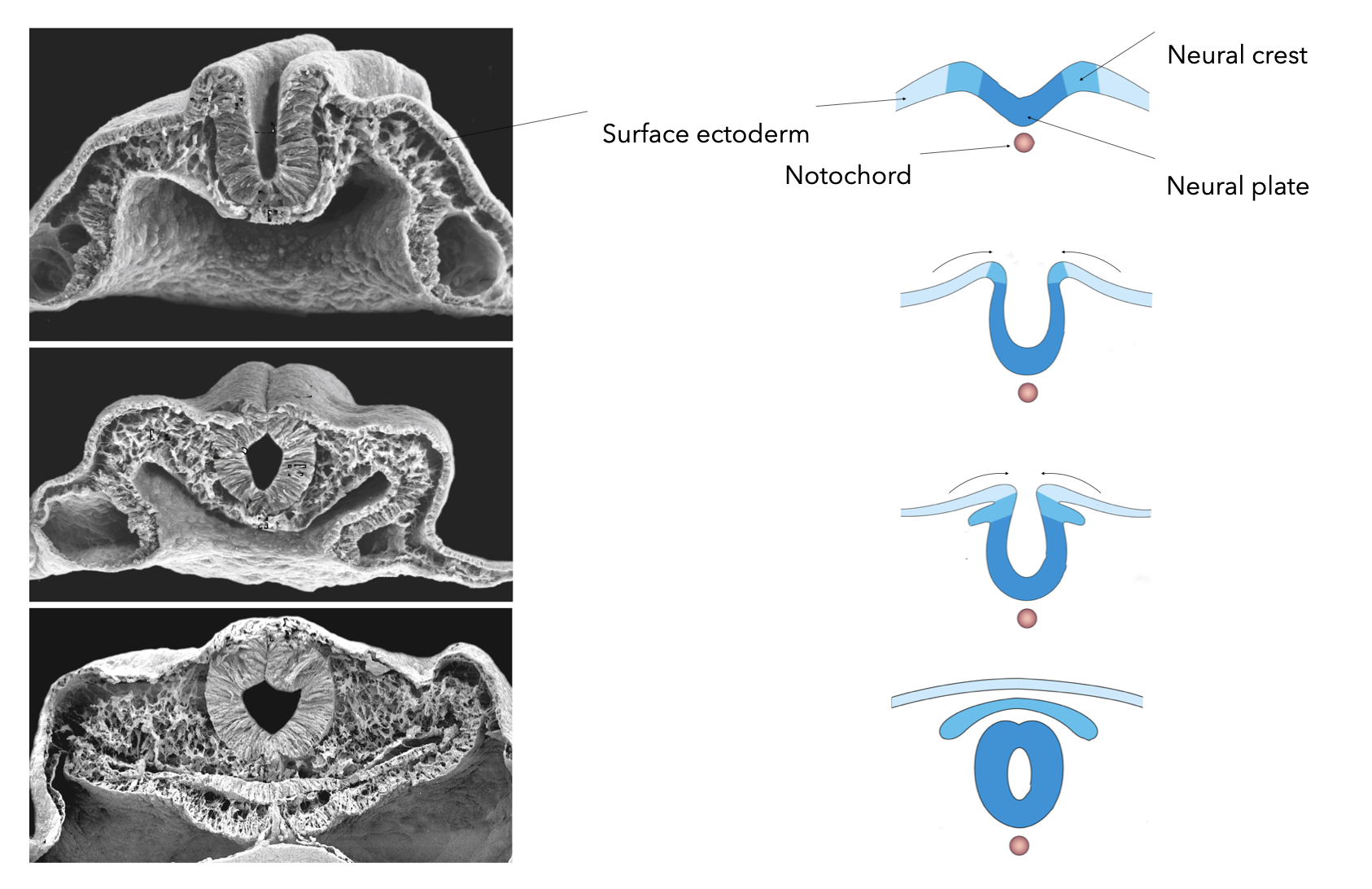

Neural tube formation

The neural plate will form a neural tube, a process that is associated with the most anomalies in development of the central nervous system. To form a tube, the neural plate undergoes two important structural changes. First, it narrows and elongates in the cranial-caudal direction. The narrowing and elongation is generated through convergent extension as described above. The second change occurs at the cellular level in which cells in the neural plate transition from cuboidal to columnar in shape. This thickens the neural plate in the dorsal-ventral axis and also narrows it laterally because as individual cells become taller they also become narrower.

To form a tube from a sheet of cells, the apical surface of the cells must become smaller than the basal surface because the inside of the tube has less surface area than the outside. To reduce the surface area of the apical surface, cells in the neural plate localize actin and myosin filaments toward their apical surface similar to columnar epithelia. Constriction of the actin filaments by myosin pinches inward the apical surface, reducing its surface area. The coordinated contraction of the apical surface of neural plate cells causes the plate to bend. The bending of the plate drives the formation of a tube.

Neural tube closure

Closure of the neural tube and its separation from the ectoderm is one of the most error-prone events during development. Closure requires that opposite ends of the neural plate to come together and associate with each other while dissociating from the ectoderm. In humans, closure starts at multiple points along the neural plate and proceeds bi-directionally from these points.

Two forces drive the edges of the neural plate together. First is the constriction of the apical surfaces of the cells as described above. The second is migration of ectoderm cells at the border of the neural plate towards the midline. As the ectoderm cells migrate toward the midline, they push the edges of the neural plate closer together.

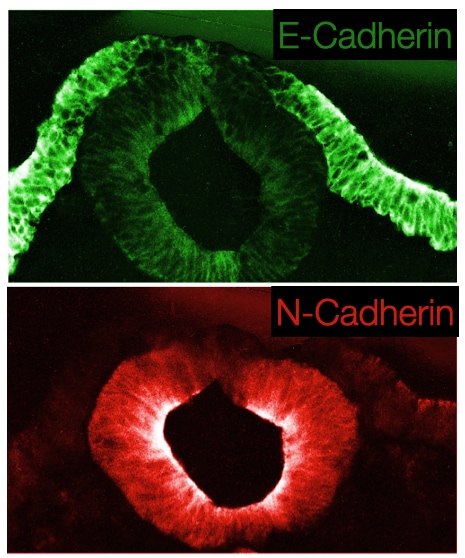

Closure of the neural tube requires that the neural plate cells dissociate from the ectoderm and associate with each other. This is accomplished in part by differential expression of E-cadherin in the ectoderm and N-cadherin in neural plate cells. The change in cadherin expression allows the neural plate cells that abut the ectoderm to detach from the ectoderm and seal the tube by associating with cells on the opposite side of neural plate that have also detached from the ectoderm.

Closure of the neural tube also releases cells from the ectoderm layer that do not join the neural tube. These cells are called neural crest cells and will develop into structures in the peripheral nervous system. Neural crest cells undergo a transition from epithelial to mesenchymal when they leave the ectoderm. This process involves decreased expression of both N and E-cadherins which allow the neural crest cells to dissociate from both the ectoderm and neural tube. The transition to mesenchymal state leads to motility in the cells, and during embryogenesis the cells will migrate to different regions of the embryo to innervate tissues that develop in those regions.

Closure defects

Neural tube anomalies arise from failure of the neural plate to form the neural tube and are among the most common birth defects worldwide varying from 0.5 to 10 per 1000 pregnancies. Most often, the failure occurs during the closure of the neural tube. Depending where along the neural tube closure fails determines the severity of the defect on development. Failure of closure in the most cranial regions (forebrain) leads to anencephaly in which the fetus lacks parts of the brain and skull. If a fetus with anencephaly makes it to term and is born, survival is usually less than 24 hours. Failure of the neural tube to close in the caudal region (future spinal cord) leads to conditions such as spina bifida, which is much less severe. People are often unaware that they have a Estimates are that 4% to 6% of the general populations has neural tube closure defects in the spinal cord, which are usually discovered during imaging of the spine for other reasons.

Cause of closure defects

Neural tube defects (NTD) can arise from either genetic causes and environmental factors. The first indication of a genetic cause of NTD came from studies on twins where higher concordance was observed in same-sex twins (which includes monozygotic and dizygotic twins) than in opposite sex twins (1.93 vs 1.00). However, the lack of Mendelian inheritance indicated that the genetic causes of NTD likely involve several genes and potentially environmental conditions.

Identifying genes involved in NTD has relied on screening for candidate genes that have been identified in mouse models of NTD or have know functions in folate metabolism. To date, no genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed for NTD. Studies of candidate genes have grouped the genes into several biological pathways, including folate metabolism, planar cell polarity (which generates convergent extension), and organization of the cytoskeleton. In addition, de novo mutations have also been found to cause NTD and many of these are in genes that encode proteins in the above mentioned pathways.

Several environmental factors also increase the risk of NTD. Nearly, 50 years ago, lower serum folate levels in pregnant females were associated with higher rates of NTD. These results and others have led to efforts to encourage females who may become pregnant to consume folic acid daily and in some countries, foods, such as bread and pasta, have been fortified with folic acid. The latter has proven more effective at reducing rates of NTD. Nevertheless, the incidence of NTD has dropped by 15% to 70% in regions where folic acid supplementation has been introduced.

How does folic acid reduce NTD? Folic acid has reduced the sex bias observed in the prevalence of NTD. Prior to folic acid supplementation, females were more likely to have NTD, but folic acid has eliminated this bias. In addition, folic acid has reduced anencephaly more than other types of NTD. However, the exact mechanism by which folic acid reduces NTD is not known.

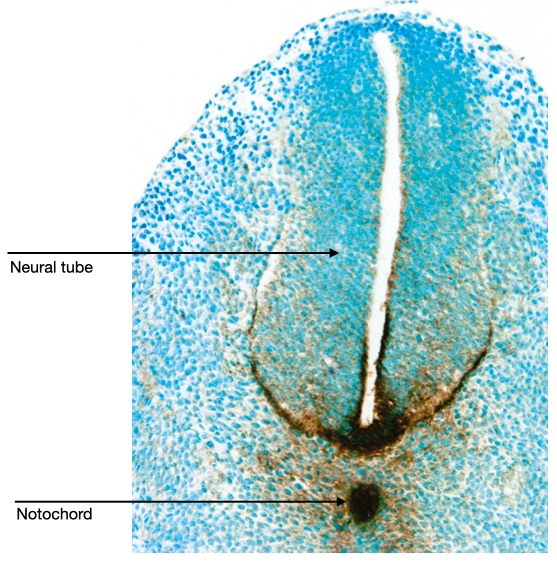

Notochord patterning of the spinal cord

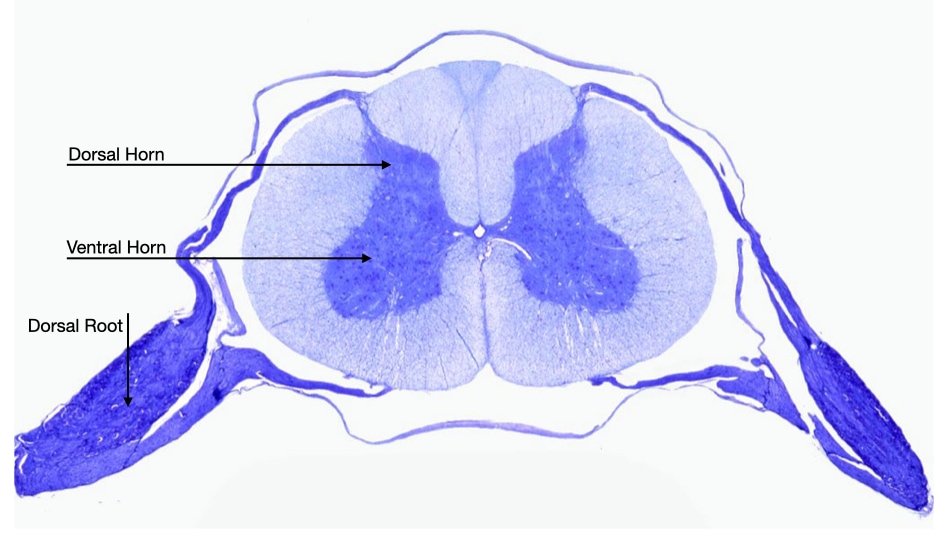

The notochord resides just ventral to the neural tube. Signaling molecules secreted by cells in the notochord affect the development of cells in the neural tube. For example, the notochord releases sonic hedgehog which diffuses across the neural tube. Cells in the neural tube which are closest to the notochord are exposed to the highest concentration of sonic hedgehog (brown stain in image below) and are induced to develop into motor neurons. Cells on the dorsal side of the neural tube are exposed to the lowest concentration of sonic hedgehog and they give rise to sensory neurons.

This pattern is reflected in the arrangement of motor and sensory neurons in the mature spinal cord. Motor neurons reside in the ventral horn of the spinal cord, whereas sensory neurons reside in the dorsal root ganglion.

Segmentation and Formation of Gut Tube

Segmentation

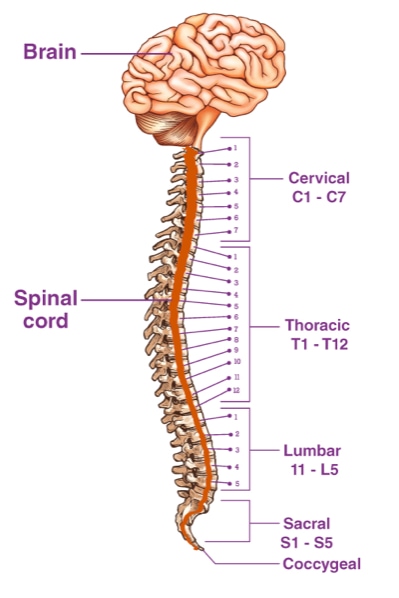

Many organisms show clear patterns of segmentation in their body plan. Worms and centipedes show a clearly observed repeated pattern of segments along the length of their bodies. In human, segmentation is less clear from outside the body, but inside the body, segmentation can been seen in the spinal cord, which contains a series of thirty-three distinct vertebrae along its length.

Although vertebrae are appear structurally similar, they have functional differences. The seven vertebrae in the neck provide structure support and facilitate movement of the head. The next twelve vertebrae connect to the ribs. The following five in the lumbar region have evolved for weight bearing. The musculature which attaches to the vertebrae also differs along the spinal cord.

Somites

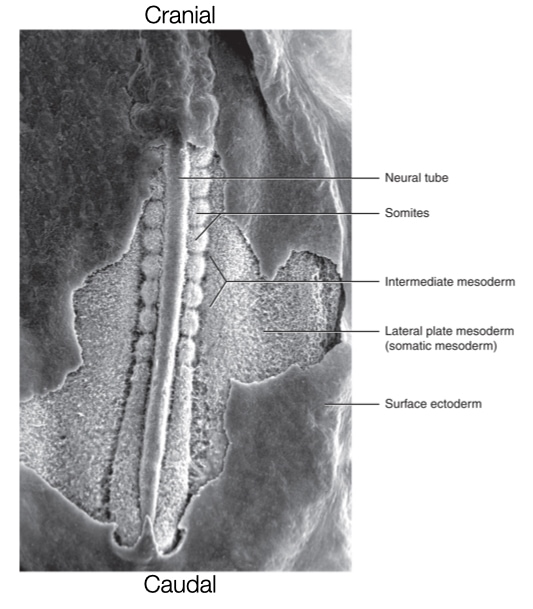

Segmentation along the caudal - cranial axis is generated through the formation of blocks of tissues called somites. Somites are transient and repeated structures which give rise to vertebrae, ribs, skeletal muscles, and dermis which is a layer of connective tissue underneath the epidermis in skin. After gastrulation, somites form from mesoderm on both sides of the neural tube. Somites form in a directional order starting from the cranial end of the embryo and extending toward the caudal end. Somites develop in pairs on opposite sides of the neural tube. Pairs develop one-by-one down the neural tube. In humans, somites develop at a rate of one pair every six hours. The regular rate of somite formation during embryogenesis allows one to measure the age of the embryo based on the number of somites.

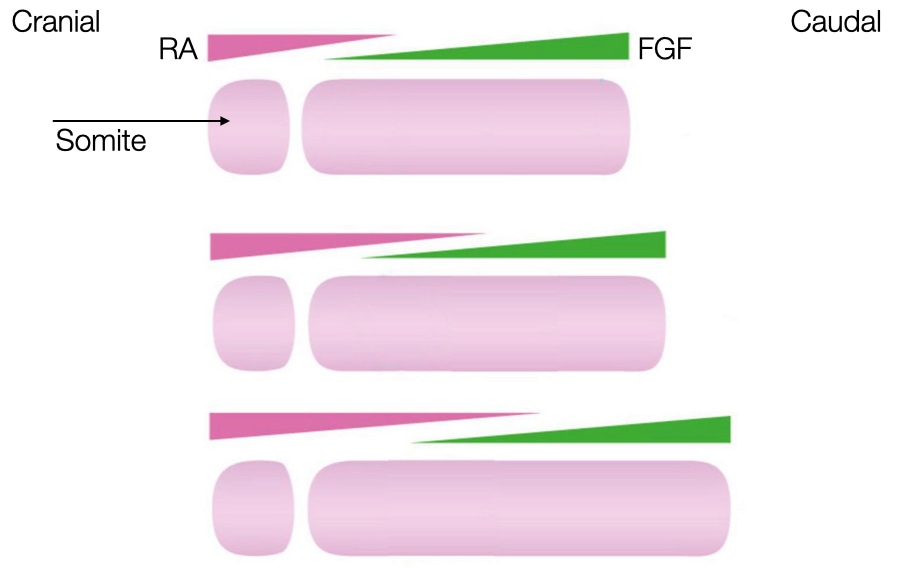

A challenged faced by the embryo is how to generate repeating, regularly spaced somites from a disorganized collection of cells in the mesoderm. One widely accepted model involves gradients of two signaling molecules and a timer.

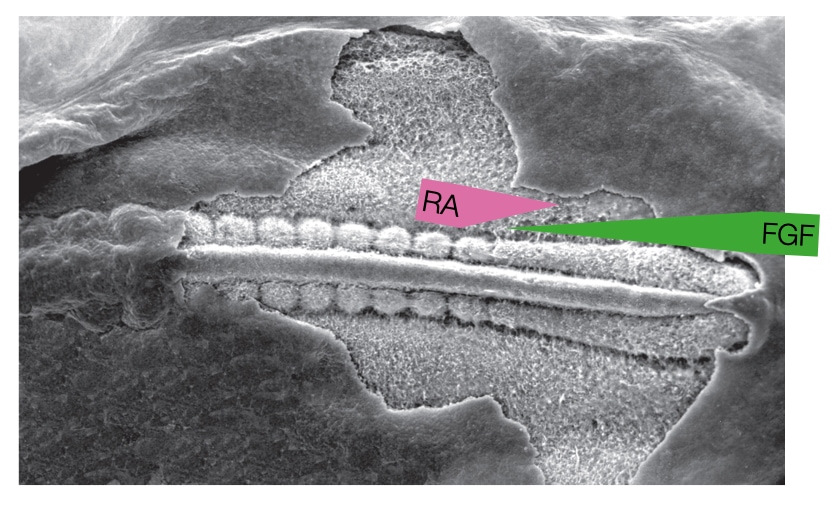

The first gradient starts from the caudal end of the embryo and involves release of the signaling molecule fibroblast growth factor (FGF). The concentration of FGF deceases as one moves toward the cranial end of the embryo. FGF keeps cells in the mesoderm in an undifferentiated state and therefore prevents cells in the mesoderm from forming somites.

The second gradient starts from the cranial end the embryo and involves release of retinoid acid (RA) from the most recently formed somite. RA concentration decreases as one moves toward the caudal end of the embryo. Retinoic acid can induce cells in the mesoderm to differentiate into somite but only where FGF concentrations are low. Thus, there is a region adjacent to the most recently formed somite that contains sufficient RA and low FGF to favor formation of a somite.

As the embryo grows in length caudally, the source of FGF moves caudally which moves the zone favorable to forming a somite gradually toward the caudal end of the embryo. The gradients of FGF and RA are sufficient to induce differentiation of mesoderm from a cranial to caudal direction but cannot generate blocks of a somites. That is because the zone moves gradually and continuously toward the caudal end, so the gradients alone would generate one long somite and not a series of individual somites.

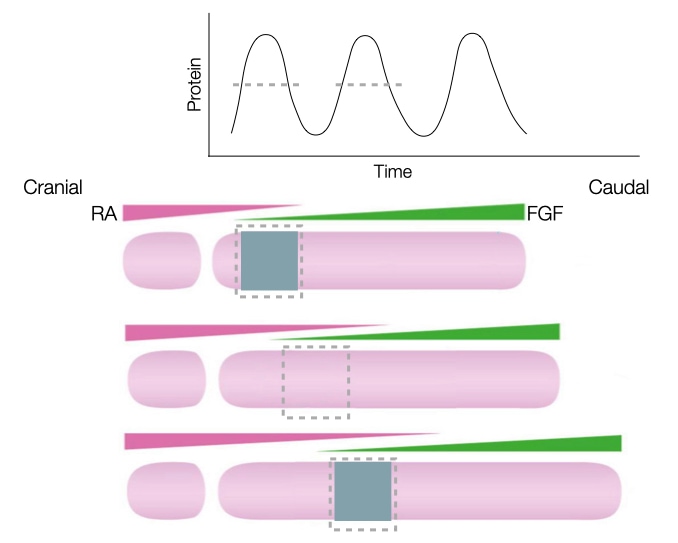

To generate individual somites, the embryo needs a timer that when on allows a region of mesoderm to become a somite when the zone of high RA/low FGF passes through it, but when off, prevents mesoderm from becoming somite even when exposed to high RA and low FGF. The timer in the embryo is an oscillation in the concentration of several key proteins in the mesoderm cells. When the concentration of these proteins is above a certain threshold, the cells can differentiate if exposed to high RA and low FGF. When the concentrations of the proteins is below the threshold, then the mesoderm cells remain as mesoderm even if exposed to high RA and low FGF.

Negative feedback in gene expression generates the oscillating patter of the timer. For example, a protein involved in making cells ready to commit to a somite fate reduces its own production by turning off transcription of its gene. When levels of the protein are low, transcription from the gene is active and the protein is synthesized. The protein levels increase to a point which makes the cells amenable to differentiate into somites if the cells are in a high RA and low FGF zone. The high levels of protein also turn off transcription, allowing degradation of the protein and its mRNA to reduce the concentration of the protein to a level at which cells no longer differentiate into somites even if they are in a high RA and low FGF zone.

This two gradient and timer system has been conserved throughout evolution because a few small adjustments to the oscillating pattern can alter the size and number of somites in the embryo. For example, if the oscillating pattern is increased in frequency, then the embryo forms many, smaller somites. Research has found that the frequency of the oscillator is much higher in organisms such as snakes compared to mammals.

Patterning Somites

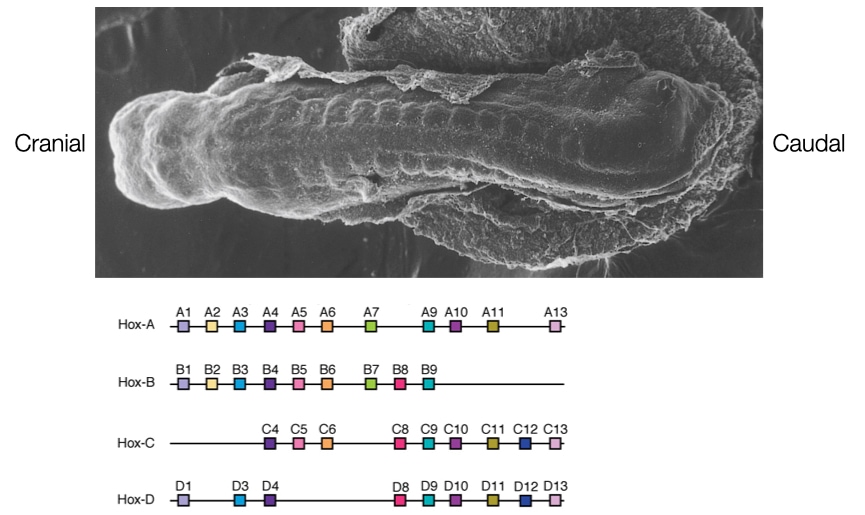

The gradient and timer are sufficient to generate a sufficient individual somites, but the somites differ cranially to caudally based on the structures their cells will generate (recall the difference in vertebrae along the spinal cord).

Another conserved mechanism generates a pattern of differentiation along the series of somites. The mechanism involves a large set of genes called homeobox genes (HOX). There are four families of homeobox genes (A - D) that are located on separate chromosomes. Each family member contains up to 13 individual genes (not all family members contain 13 genes). Related genes have the same order within the families (i.e., A1, B1 and D1 encode related proteins). The genes appear to be activated in the order that they reside in the chromosomes from 1 to 13 with lower number genes being activated first. Activation of the Hox genes also depends on when the mesoderm cells descended through the primitive streak. Cells which descend first form the most cranial mesoderm and those that descend later form more caudal mesoderm. Thus, cells that descend first and occupy cranial spaces will express the lowered number Hox genes. Cells that descend later and occupy more caudal spaces in the mesoderm will express higher numbered Hox genes.

As a result, the expression of Hox genes varies along the length of embryo with cranial somites expressing low numbered Hox genes and caudal somites expressing higher numbered Hox genes. This difference in gene expression determines different patterns of tissue formation along the length of the somites.

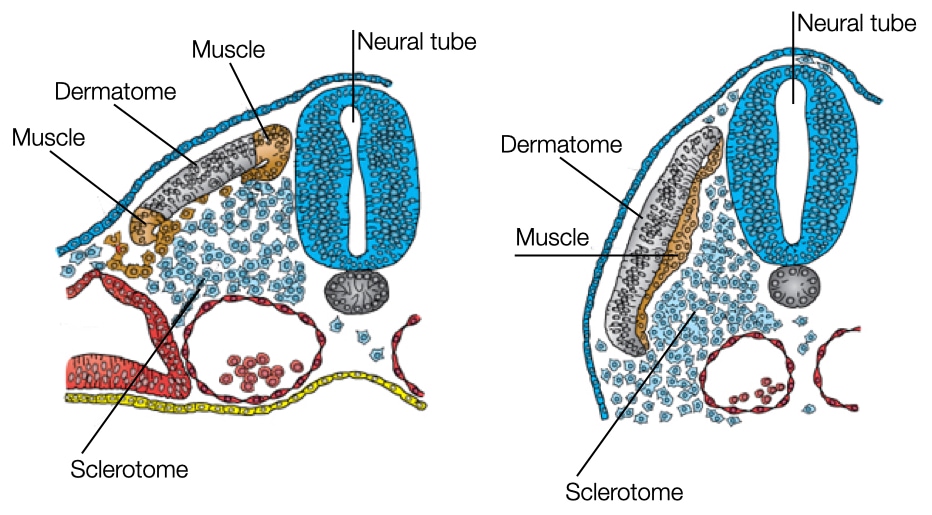

Differentiation of Somites

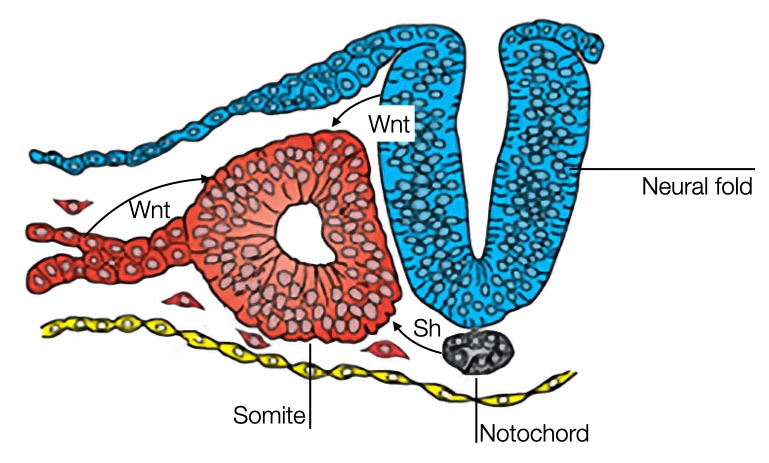

Cells in somites give rise to several different structures and tissue types, including vertebrae, muscle and dermis in the skin. Different regions of the somite develop into these structures based on their exposure to different signaling molecules. Signaling molecules released from surrounding structures will determine the fates of cells in somites.

When somites first form, the cells resemble fibroblasts and form a ball of interacting cells. These cells transition into epithelial-like cells and assemble into a structure with a central cavity. Under the influence of different signaling molecules, the epithelial cells will transition again into cells with different fates.

One signaling molecule is sonic hedgehog which is released by cells in the notochord and at the ventral side of the neural tube. Sonic hedgehog diffuses and impacts cells in the somite closest to the notochord and neural tube. Sonic hedgehog causes these cells to dedifferentiate into mesenchymal cells and dissociate from the somite. Eventually, the cells will form the vertebrae and ribs.

The remaining cells in the somite will be influenced by Wnt to develop into muscle tissue. Cells in the dorsal side of the neural tube secrete Wnt which affects cells in the somite closest to the dorsal region of the neural tube. In addition, mesoderm located laterally to somite also secrete Wnt which affects the cells on the lateral side of the somite. Between these two regions in the somite is an area of cells that is exposed to low concentrations of Wnt. These cells will differentiate into a structure called the dermatome which will form a connective tissue layer in the skin called dermis.

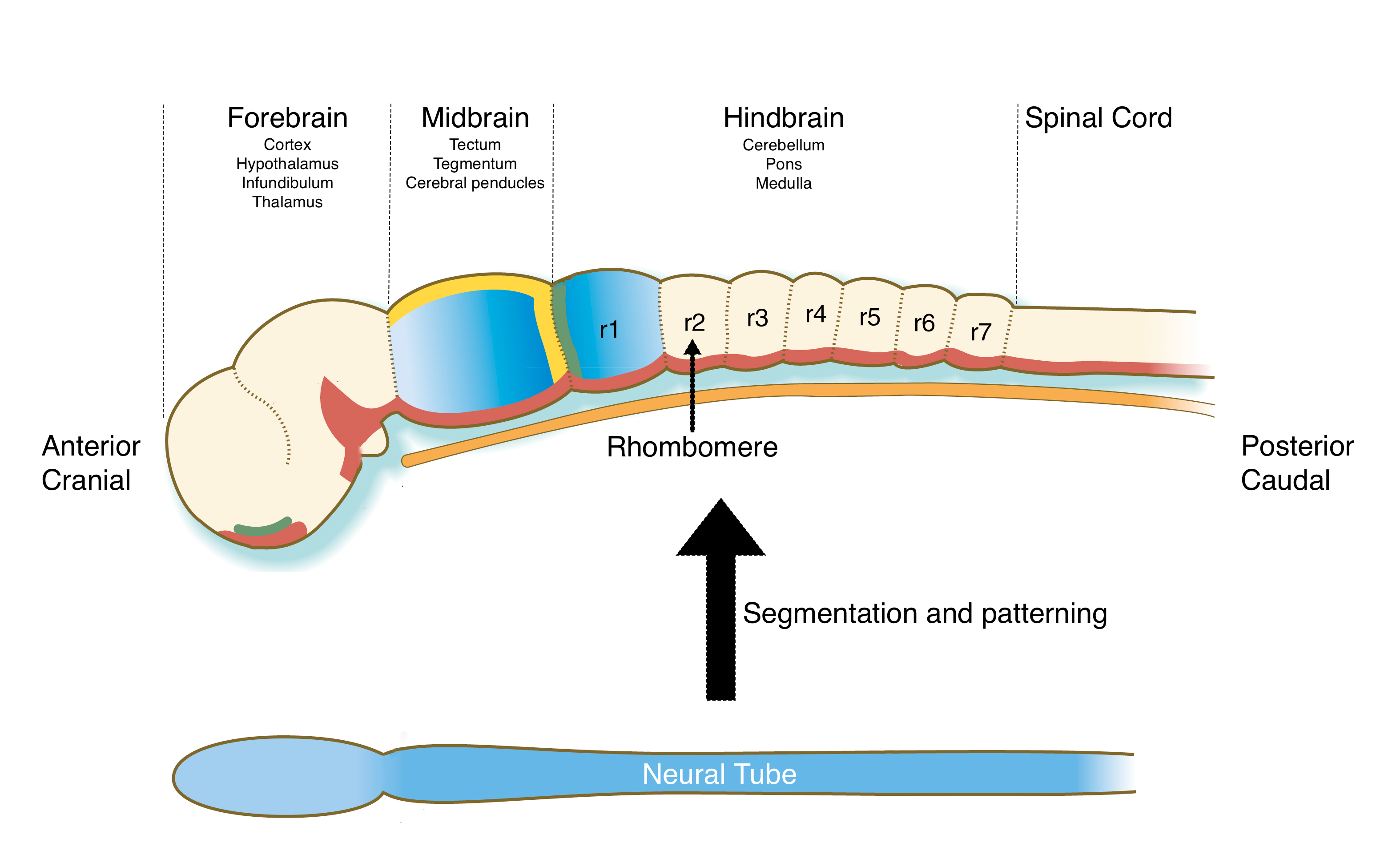

Patterning the Neural Tube

Recall that the neural tube forms from ectoderm and runs from the cranial end of the embryo to near the caudal end. Cells in the neural tube will develop into all the neurons and support cells in the central nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord. Because different regions of the brain and spinal cord perform different functions, the neural tube is segmented into different regions during development. The major regions that initially form are the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), hindbrain (rhombencephalon) and spinal cord.

Here, we’ll focus on patterning of the hindbrain. The hindbrain is not only essential for the development of the future cerebellum, pons and medulla in the brain, but it also produces neural crest cells that will help form craniofacial structures, such as the jaw.. Mutations or teratogens that affect patterning of the hindbrain or production of neural crest cells can lead to malformations in structures in the face. During development, the hindbrain regions of the neural tube is patterned into a series of blocks tissue called rhombomeres. Each rhombomere is considered a distinct developmental unit which will give rise to neurons with different functions and neural crest cells that generate different structures in the head and neck.

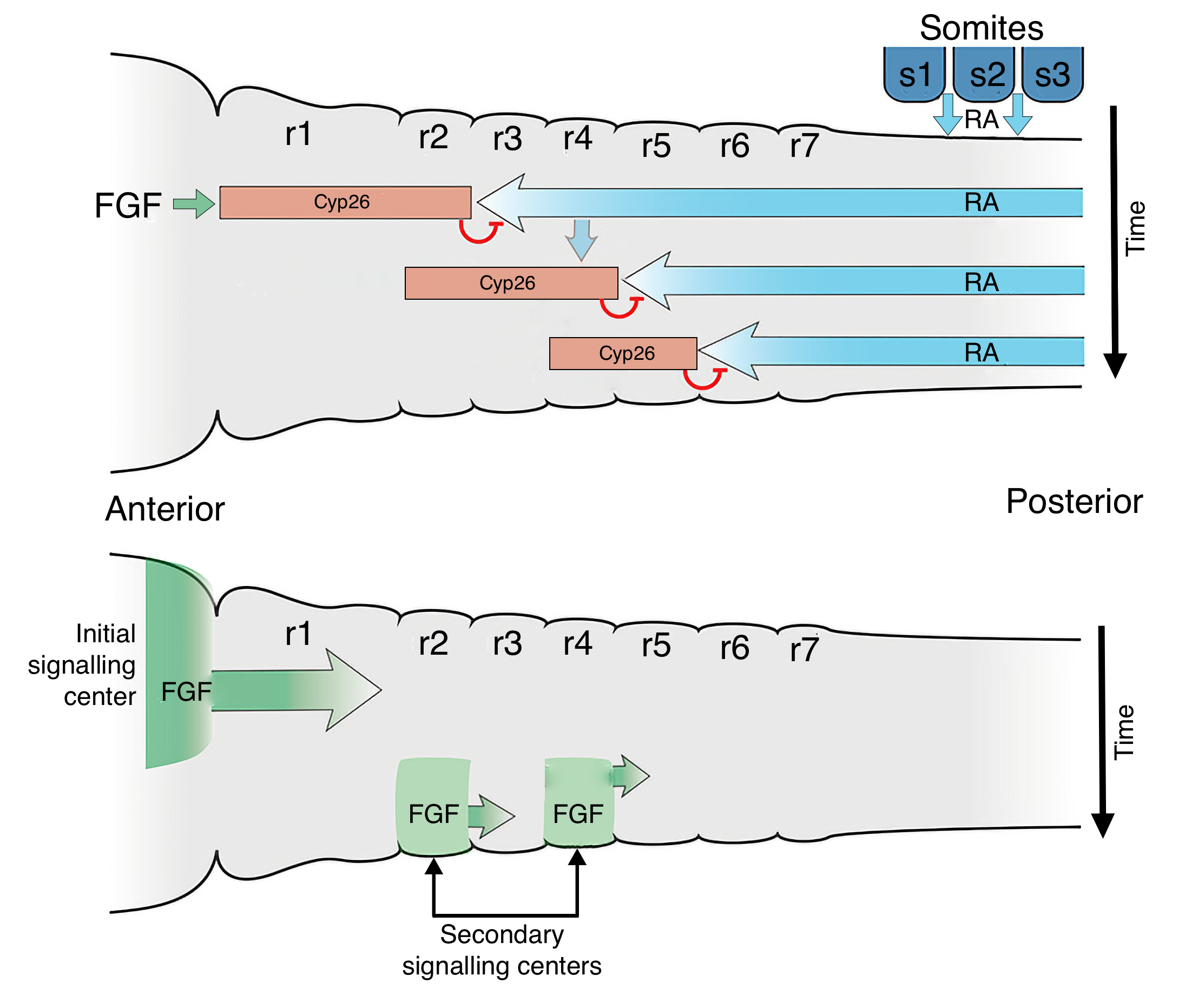

The patterning of the hindbrain uses a similar mechanism as segmentation of mesoderm into somites. Gradients of FGF and retinoid acid (RA) will establish an anterior-posterior axis along the hindbrain and somites have a key role in generating this gradient. The anterior most somites, which are located toward the caudal (posterior) end of the hindbrain region of the neural tube, produce RA. RA diffuses both caudally where it induces formation of somites and cranially (anterior) where it keeps cells in the neural tube in an undifferentiated state. FGF is produced by cells at the border between the midbrain and hindbrain and diffuses caudally. Where FGF concentrations are high, cells produce an inhibitor of RA called Cyp26. Thus, the region of hindbrain closest to the midbrain is exposed to low concentrations of RA and begins to differentiate into rhombomeres. Once formed, the rhombomeres produce FGF, which decreases RA concentrations in the adjacent caudal region of the neural tube, allowing it to form rhombomeres. This process proceeds down the hindbrain to form seven rhombomeres. Each rhombomere will develop cells with different functions based on expression of different Hox genes.

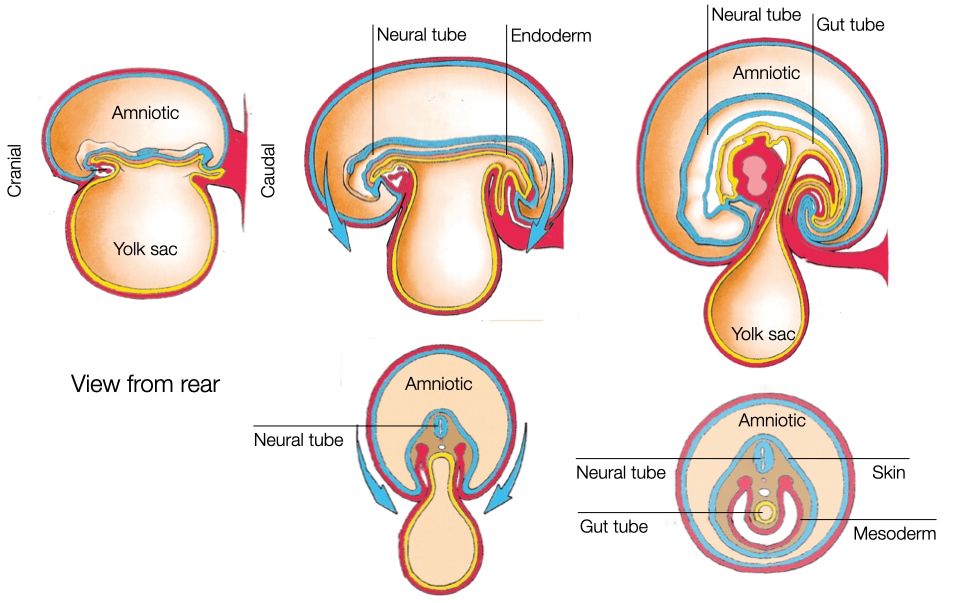

Formation of the Gut Tube

As the embryo develops, it lengthens in the cranial-caudal direction due to convergent extension and cell division (see the second embryology lecture for details). While the embryo lengthens, the yolk sac underneath the embryo doesn’t increase in size. As a result, the embryo begins to fold inward at its cranial and caudal ends and grow toward the center to accommodate its larger size. At the same time, the embryo also begins to fold inward laterally. The folding along the four edges of the embryo brings the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm layers inward on the ventral side (facing the yolk sac) of the embryo. As those layers are drawn inward, the connection between the embryo and yolk sac is pinched together until all that remains is a narrow duct that connects the embryo to the yolk sac. This structure will eventually develop into the umbilicus.

The folding generates a tube within the embryo that is surrounded by endoderm. This structure is called the gut tube and will develop into all of the structures of the GI tract, including esophagus, stomach and intestine.

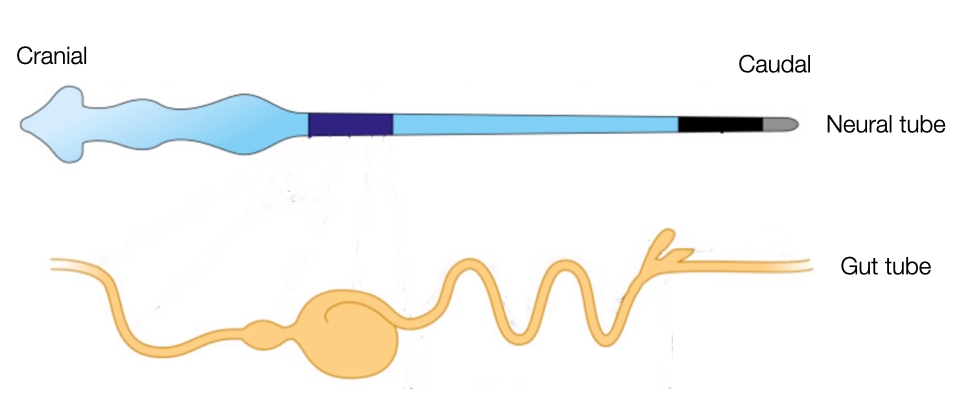

After the folding complete, the embryo is surrounded by a layer of ectoderm (future skin) everywhere except at the site of the future umbilicus. Internally the embryos contains two tubes that run cranial to caudal: neural tube and gut tube.

The neural tube and gut tube run parallel to each other along the cranial-caudal axis of the embryo. The close proximity of the tubes is important because cells generate during closing of the neural tube, neural crest cells, migrate through the mesoderm to reach the gut tube. Once there, the cells will form ganglion of neurons along the wall of the gastrointestinal tract to control peristalsis and the secretion of acid and other factors.